Regenerative treatments for back and neck pain – platelet rich plasma (PRP) Platelet rich plasma (PRP) injections have been around since the 1990s when they were used in maxilla-facial and plastic surgery.

Regenerative treatments for back and neck pain – platelet rich plasma (PRP)

Platelet rich plasma (PRP) injections have been around since the 1990s when they were used in maxilla-facial and plastic surgery. More recently, PRP injections have become popular for treating soft tissue injuries that can result in neck and back pain. Several elite athletes such as Tiger Woods and Rafael Nadal having undergone PRP treatment and some cite PRP injections as the reason for their speedy return to play after injury.

PRP injections work by stimulating healing in tendons, ligaments, muscles and joints through the activation of growth factors and reparative processes. This can then help to enhance function and reduce pain associated with soft tissue injuries and dysfunction.

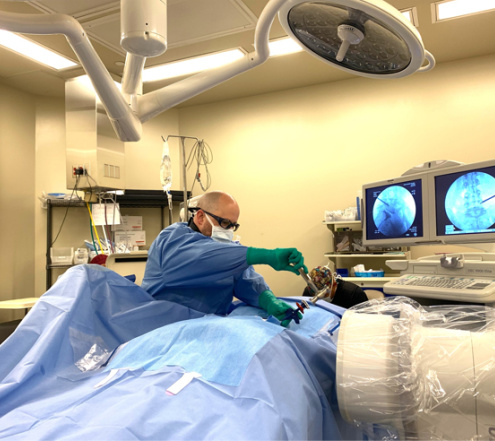

The technique involves the use of a patient’s own blood, which is drawn and then centrifuged to separate the activated platelets. This platelet rich plasma is then injected into the area of tissue damage in order to stimulate repair. Ultrasound imaging may be used to help ensure that the injection reaches the intended site.

As the patient’s own blood is used there is no risk of rejection of foreign material, making PRP treatment a generally safe form of therapy.

This article will look more closely at the following issues regarding platelet rich plasma (PRP):

What are platelets, and what is PRP?

Platelets are an extremely important part of the blood and are involved in wound healing and clot formation. They contain natural growth factors such as platelet derived growth factor (PDGF), insulin like growth factor (IGF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), platelet derived angiogenic factor (PDAF), and transforming growth factor beta (TGF-ß). They also contain other substances that are important for wound healing, such as fibronectin.

Platelet rich plasma (PRP) is sometimes referred to as autologous platelet gel, plasma rich in growth factors (PRGF), or platelet concentrate (PC). PRP is created by collecting a patient’s blood and centrifuging it at varying speeds for around 12 minutes in order to separate it into three fractions: platelet poor plasma (PPP), (platelet rich plasma (PRP), and red blood cells.

A platelet activator (agonist) is then added to the PRP, typically in the form of bovine (cow) thrombin and 10% calcium chloride. This activates the clotting cascade and produces a platelet gel with a platelet concentration around 3-10 times that of ordinary plasma (Wang & Avila, 2007).

How does PRP work?

PRP is a source of numerous factors that are essential for healing, such as substances that enhance cell recruitment, multiplication and specialization. Specifically, PRP contains PDGF and epidermal growth factor, both of which are key to the synthesis of collagen and the activity of fibroblasts – essential elements in wound healing. Some research suggests that healing of soft tissue may be 2-3 times faster than normal in the presence of increased concentrations of these growth factors (Anitua et al., 2004).

PRP is considered by some to be a more comprehensive strategy to promote tissue regeneration, compared to the administration of single recombinant human growth factor. The substances found in PRP are thought to help speed up the growth of blood vessels to new tissues and enhance the creation of new scaffolding for bone and soft tissues, thereby supporting bone regeneration, wound healing, and cartilage repair.

What are the benefits of PRP?

PRP is relatively inexpensive and accessible as it is an autologous treatment.

PRP may be particularly useful in spinal fusion procedures as it has been seen to improve the ability to pack particulate graft materials, thereby helping to maintain space and support bone regeneration (Wang & Avila, 2007).

Some further potential advantages of PRP suggested by research include (Wang & Avila, 2007):

- Improved graft adhesion

- Reduction in micro-movement of graft

- Accelerated wound healing, including epithelialization

- Decreased scar formation

- Increased osteoblast activity (osteoblasts are bone-building cells)

- Angiogenesis (increased blood vessel growth).

Studies in humans are still insufficient to provide an accurate picture of the effects of PRP, but early studies have shown that treatment with PRP enhanced healing and bone regeneration (Anitua, 1999; Marx et al., 1998).

Is PRP safe?

Because PRP is derived from the patient themselves (an autologous treatment) it poses no risk of cross reactivity, disease transmission, or immune reaction, depending on the treatment protocol (Wang & Avila, 2007).

However, the use of bovine thrombin as an activating agent for PRP could prompt a reaction by the immune system, in addition to making such treatments unsuitable for those who avoid cow-derived products (Landesberg et al., 1998).

PRP is a source of numerous growth factors, and while these are necessary for timely healing, they may also have a cancer-promoting effect. PRP injections work in part by increasing the initial inflammatory stage of healing, which could mean that a patient experiences a temporary increase in pain and swelling at the injection site. As such, patients are usually recommended to temporarily halt their use of anti-inflammatory medications in order to optimize results when undergoing PRP treatment.

In summary

Platelet rich plasma injections are a relatively new treatment for back and neck pain, with promising results seen in animal studies and in early trials in humans. These injections appear to work by triggering the body’s natural healing response, helping to repair damaged tissues such as ligaments, tendons, spinal discs, and bone that may be contributing to pain and dysfunction.

While further studies are needed, PRP injections may offer a cost-effective, relatively safe and accessible form of treatment for back and neck pain.

References

Anitua, E. (1999). Plasma rich in growth factors: preliminary results of use in the preparation of future sites for implants. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants, 14:529–535.

Anitua, E., Andia, I., Ardanza, B., Nurden, P., Nurden, A.T. (2004). Autologous platelets as a source of proteins for healing and tissue regeneration. Thromb Haemost, 91:4–15.

Landesberg, R., Moses, M., Karpatkin, M. (1998). Risks of using platelet rich plasma gel. J Oral Maxillofac Surg, 56:1116–1117.

Marx, R.E., Carlson, E.R., Eichstaedt, R.M., Schimmele, S.R., Strauss, J.E., Georgeff, K.R. (1998). Platelet-rich plasma: Growth factor enhancement for bone grafts. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod, 85:638–646.

Wang, H-L., & Avila, G. (2007). Platelet Rich Plasma: Myth or Reality? Eur J Dent, Oct; 1(4): 192–194.